There has been a lot of excitement in the life insurance industry over the potential applications of liquid biopsies. This is a test on a blood sample which can detect circulating cancer DNA.

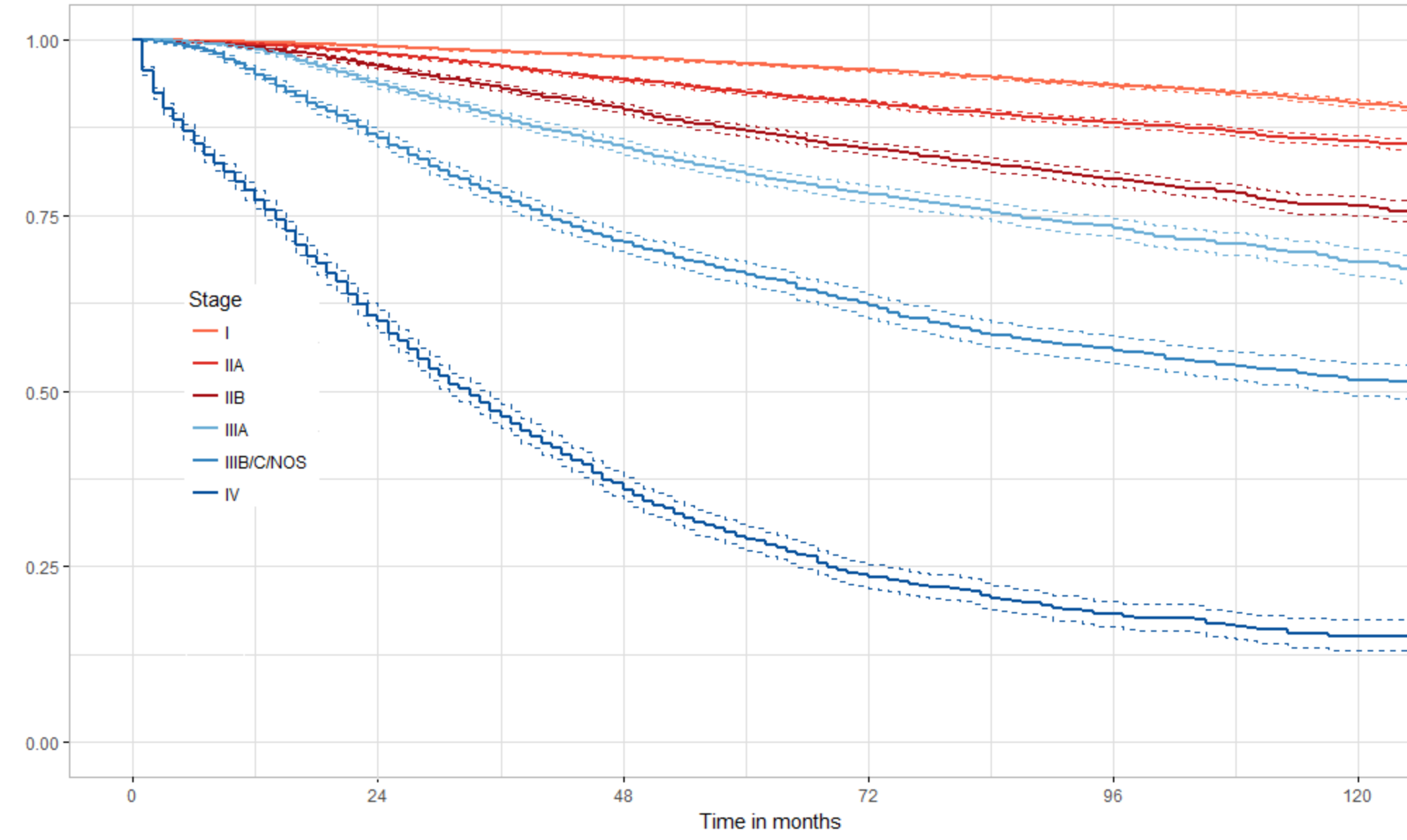

In a pair of editorials in the journal Cancer recent developments in the field are presented. Part 1 is of particular interest, as it discusses the potential use of liquid biopsy as a screening test in the general population. It was very gratifying to see the the principal researcher, Dr. Papadopoulos, was cautious in his approach despite the 99% specificity. As he pointed out, though 99% sounds good, it is not sufficiently high for general population screening, where the prevalence of cancer is low. It was also noted that the test is much better at detecting late-stage cancer than early-stage cancer. This may be a problem, since early detection is what is needed to drive down mortality rates.

This particular weakness may actually be a strength if the purpose is life insurance testing. One of the main goals of testing in the life insurance industry is to guard against possible anti-selection. Because even late-stange malignancies may not cause abberations in the standard laboratory panel, current testing regimens may not be able to detect malignancy in those who do not know or do not want to admit that they have cancer. The liquid biopsy, however, if it is sufficiently inexpensive, may fill this need. Certainly, more research is needed before any conclusions related to population or life insurance testing can be reached.

Part 2 of the series deals primarily with the possible change in the way that Pap tests are done. Some new research has shown that Pap tests done with a different collection brush combined with liquid biopsy technology can detect cervical, endometrial and even some ovarian cancers. This is exciting because ovarian cancer really has no good screening test and is the 4th leading cause of cancer deaths in women. Again, caution is needed because this is not the first time that a promising screening test for ovarian cancer has come around, only to be found to be useless later on (CA-125).